Listen to the Podcast Here:

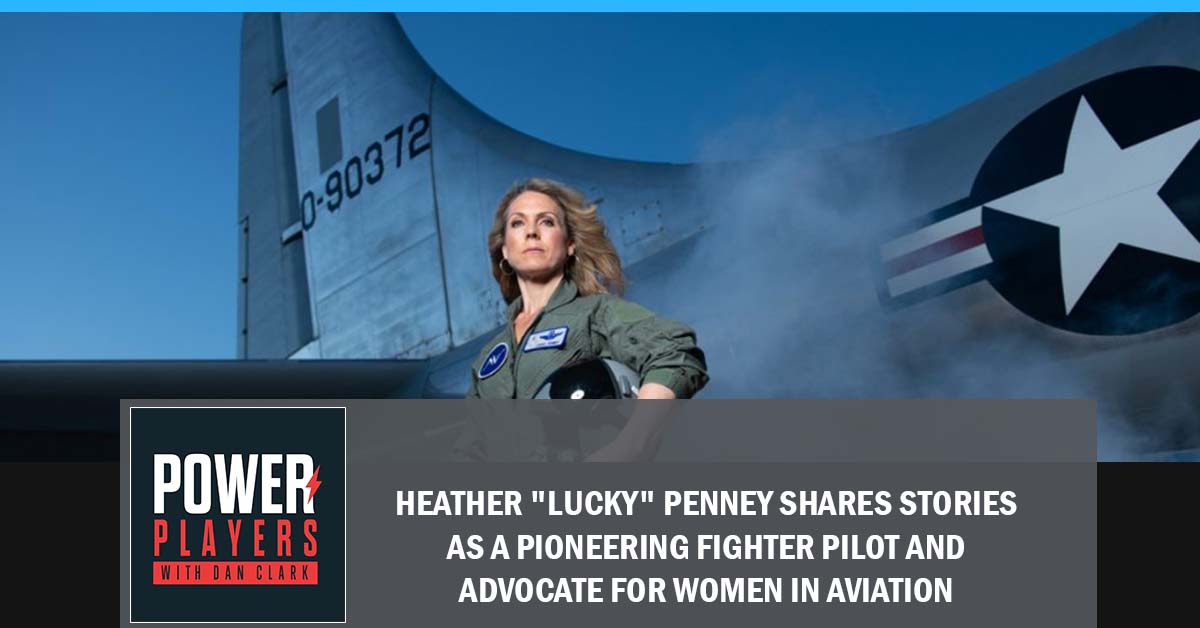

Aviation is one of the industries where women are underrepresented. Our guest today is an aviation pioneer who now spends her days as an advocate for women in aviation. Most widely recognized for her service on September 11, Heather “Lucky” Penney was part of the pioneering first wave of women who entered fighters directly from pilot training. Heather’s passion for aviation has never faded. She is a passionate advocate for aviation, women in aviation, aviation history and museums, and the future of aviation. And she still flies a cool selection of planes. Join here to get more of her story.

—

Heather “Lucky” Penney Shares Stories As A Pioneering Fighter Pilot And Advocate For Women In Aviation

This is an interview with the brave and devoted patriot pilot, Heather Penney. Thanks so much for spending some time with me. In this episode, my dear friend and real-life superhero, Heather Penney, a US Air Force F-16 pilot, who was called into action on September 11th, 2001, to defend the capital region from further attack, shares her life and the details of what was expected of her on that horrific day giving us an inside glimpse into the mindset and heart set of a fearless warrior willing to sacrifice herself so that others may live.

—

You are a role model for everyone I’ve ever met. Your ability to connect is so incredible. Let’s get right to the story. The first P is Passion. When you are called upon an extraordinary circumstance, talk to us about what drives us to exceed expectations to perform under pressure. As you answer that question, take us back to exactly what was happening as a 25-year-old lieutenant on guard on that beautiful, clear Tuesday morning on September 11th, 2001. Paint the picture and give us that whole scenario that unraveled and unfolded for you that morning.

You talk about passion and flying the F-16 was my passion. It was my why. For people to discover your passion, it requires a curiosity and a willingness to try new things to see what creates that fire inside of you. I had been fortunate enough that my father was an Air Force fighter pilot. That curiosity or little spark had caught fire early on in my life. I knew that I wanted to be a fighter pilot and there was a greater purpose behind that. That is what created a devotion for me.

As I applied myself through pilot training, I loved the challenge. I loved that it was hard. I loved that there was a community of belonging or a brotherhood where we helped each other out with that, but the sheer application of learning my trade, meeting the challenge and honing my skills brought me such joy and satisfaction internally. More than that, it was knowing that was in service to others and as I got better at my craft, that would be in service to our nation. As a young fighter pilot, I was on fire for this.

In 2001, I’m 25 years old. We’ve gotten back from a deployment to Red Flag. Our squadron is virtually empty because everyone’s taking leave to be with their family. We’re a national guard squadron, so the part-timers were off back to their real jobs. It was a perfect flying day. It was a crystalline blue sky and not a cloud in the sky. There were light winds out of the Southwest and barely five knots. It was spectacular but I was stuck in a scheduling meeting.

I was doing the queep of running the fighter squadron. It’s not that I was running it but I was there supporting my director of operations, Marc Sasseville. We had our weapons officer, Razin Caine, going over the basics and the motherhood of running the fighter squadron as we got back to our regular pace. That’s what that morning looked like to me. Like everyone else who woke up that day, it began completely normal, ordinary and nothing out of the usual.

Women In Aviation: Once that second plane flew into the second World Trade Center and it was on purpose, that was when everyone knew that the world had shifted.

You’re kicking back, having your cup of coffee, shooting the bull and doing the administrative work. The television sets on and what happens?

We were in our meeting. A knock came on the door and this enlisted troop barges in on the meeting, which is pretty unusual. He says, “Someone flew into the World Trade Center.” We looked out the window and thought, “How does that happen?” D.C. and New York typically share similar weather patterns, so we expected it to be bright blue in New York as well. We made a couple of morbid jokes because in our trade, having a somewhat ironic sense of humor is helpful. We assumed that it was maybe a tourist airplane going down the Hudson bumped into a building and it wasn’t that big of a deal. We didn’t have any additional information. We assumed that it wasn’t that bad and went to our meeting.

It wasn’t until the second aircraft hit the second Trade Center. The troop came back in. He didn’t even knock this time. He said, “Another plane flew into the other tower. It was on purpose.” That was when we knew the world had shifted. We got up, went to our bar where the television was and saw what everyone else saw that morning, those images. We knew that we had to get our warrant. We had to protect the Capitol.

That’s your job in the D.C. area at the joint base. I’ve been there many times. I know the proximity so that is your job to protect the Washington D.C. airspace as the year national guard.

It wasn’t. Not at the time. It is now. There’s a very robust alert squadron. There are jets on the station ready to go. There are guys in the alert shack ready to run out and take off at a moment’s notice. Also, it’s not just the jets. There are several layer defenses, rules, trigger points and so forth but in September of 2001, we lived in a world after the Cold War had ended. If you recall, the world was flat. It was post history and unipolar. We were the only great power in the world. We were preparing to go do Northern and Southern Washington Watch, which was being a peacekeeper in the sky over Iraq as part of the consequences after Desert Storm of ‘91. That was our job.

As we stood there, we knew that we needed to get airborne. We also realized we had no armament on the jets because we were preparing to go do Northern and Southern Watch. We had practiced ammunitions. We had captive air training missiles. It’s a tube with electronics in it. There’s no rocket motor and explosives. We don’t carry around live bombs and missiles.

Make it so that as you got better at your craft, you would be in service to your nation.

We had nothing on the jets that would have prepared us to protect our nation’s capitol in the way that you would have expected. All that we had was 105 rounds of training bullets and not high explosive incendiary rounds. It’s a very big BB gun. It’s 105 rounds of lead nose training bullets and that’s all we had on the jets.

You’re standing there with your commander. There are two of you. Are there ten jets airborne or is just you and your commander?

We had sent a three-ship to go do their basic service tax, some of the training that we were doing to prepare for our upcoming deployment. They were down in North Carolina off the Cape Hatteras. That was Lou “Shooter” Campbell, Eric “Puck” Haagenson and Billy Hutchison. There were probably about 5 or 6 of us pilots total in the squadron. Marc Sasseville was the Director of Operations. All of our jets were sitting on the ramp and even the three-ship, a bully flight, had practice ammunitions as well. They didn’t have any real weapons or bombs. Also, they were still living in that pre 9/11 world because they had taken off before the towers were hit. They had not seen the images.

The biggest problem was that because it was not our job in that era to protect the nation’s capitol and we were the National Guard of Washington, D.C., the District of Columbia, we didn’t have a governor. Our chain of command runs to the president. As you can imagine, he was pretty busy at the time. There was no organizational structure that could authorize us to launch immediately and that was our biggest problem. We needed to get the authorization to take off. Our next problem was we needed to get our jets armed with real ammunition or weapons. By the time we got the authorization to launch, it came from Vice President Cheney. He thought, “I fly out of Andrews all the time. Aren’t there fighters on Andrews? Somebody gets them airborne,” but that authorization didn’t even come until after the Pentagon was hit.

You remember the timeline. The towers were hit and then the Pentagon was hit. We didn’t even have the authorization in time to protect the Pentagon. Thank goodness we finally got the call from the Secret Service authorizing us from the vice president to be able to launch but by then, we still were not able to get the jets loaded up with weapons, so when Marc Sasseville looked at me and said, “Lucky, you’re with me,” we knew that we were on a one-way mission. We had to take off with no weapons on board.

The word came in that there was another hijacked jet heading towards Washington, D.C. with every intent and purpose to take out the White House or the Capitol building. Is that the intel you got?

Women In Aviation: During 9/11, there was no organizational structure that could give the authorization to immediately launch. That was the biggest problem. The pilots needed to get the authorization to take off.

Yes. We had been talking with the Potomac Approach Air Traffic Control. Our Intelligence Section had been working with the FAA trying to identify all the aircraft that had landed because by then, the FAA was landing everybody and trying to identify what aircraft were or were not accounted for. At the time, we thought there were multiples but the intel that we had gotten from Potomac Air Traffic control was that there was one airliner inbound and they thought it was low and coming down the river.

That was the United Airlines jet. That was the intel that included that.

We did not know that it was United and also the flight number. We just knew that there was an airliner coming down inbound towards the Potomac River. By then, we had already brought the bully’s home. We had called down to the practice range and told the three-ship of F-16s down there to come home. Puck had already landed. Shooter and Billy were coming in and they were landing as we were getting the authorization to launch.

Shooter didn’t have enough fuel to take off again but Billy did. Billy was the very first jet airborne to go look up over the river but he didn’t have a whole lot of gas. He takes off. Sass and I are taking off seconds after him. Billy takes off, heads up the Potomac to about Great Falls, turns around, heads on down to where the Potomac turns into the Chesapeake, then comes back in and lands. Sass and I had full tanks of gas, so we took off and spread wide, searching low and headed out Northwest over Pennsylvania but we never found it.

In search of this rogue jet that you knew you had to take out, that was your assignment. How did you and your wingman communicate to each other that it was a one-way kamikaze mission? How did that go down?

We had talked about it before we had gotten that and while we were waiting for the authorization. Sass, who is my flight lead and was the director of operations for the squadron, myself, Razin Caine, who was our weapons officer, and Igor Rasmussen, who was another wingman, we had done a quick briefing to figure out how we would weaponeer this. What could we do? What were the most vulnerable elements of an aircraft or the airliner? We realized that what we had was not sufficient. We knew then that we would need to be ramming the jet if we were not able to get missiles on board in time.

There are things in this world that are more important than ourselves.

When Sass and I were grabbing our flight gear, Sass looks at me and goes, “I’ll take the cockpit.” I knew I would take the tail. When he said, “I would take the cockpit,” what he was saying was that he was going to ram his jet into the cockpit to take out the terrorists and I would ram the tail to take the tail off of the airplane because, without the tail, an airplane can’t even glide. It becomes unbalanced and goes straight down. We knew that if we were successful, we would not be coming back.

Your passion for flying drove you to become an F-16 pilot. In a man’s world, you excelled and gained the respect and admiration of everyone with whom you worked and flew. All of a sudden, your passion for flying puts you in the most incredible unprecedented predicament. You have to make the ultimate sacrifice perhaps to save our country. To save thousands of lives, you’re willing to make the ultimate sacrifice and take your life.

That brings us to the second P. How did you prepare for that? Who inspired you to prepare to live through integrity first, especially service before self and a commitment to excellence in all you do? What did you do specifically, mentally, physically, spiritually and emotionally to prepare yourself for this occasion? As you tell this story, everyone with whom we capture on this show will have already experienced the so-called COVID crisis. Some of them have the, “Whoa me. Oh my gosh. You have no idea how hard this was.” All of a sudden, you come into the scene as superwoman, wonder woman or wonder man as the generalist hero you are.

Teach us about what you went through to prepare yourself. This would be a powerful place for you to answer the question when asked why you were ready to fly a kamikaze mission. How did you answer that? I’ve heard you say that in your speeches. Consolidate that powerful quote and then embellish your mental, physical, spiritual and emotional preparation to allow you to step up in this amazing challenge.

There are things in this world that are more important than ourselves. If I were to consolidate everything that you’ve asked, it would be in that bit. There are things in this world that are more important than ourselves, personal safety and self-interests. That’s what I find so inspiring about that story. I’m not a hero. First of all, Sass and I didn’t make it in time. The passengers on Flight 93 are the real heroes. They made the sacrifice.

I had listened to mission tapes from my father’s sorties in Vietnam and that was part of where I realized that there was a greater purpose or meaning behind flying fighters. It wasn’t just the thrill and the adrenaline of flying this high-G mock jet. It was about what I could do with that to serve our nation that made me so passionate about it and drove me to practice my skills, meet the challenge and stay committed even when I didn’t get it right, I made mistakes, it was hard and boring. I was still passionate because it was purposeful. I had raised my right hand and sworn an oath to my country to be prepared to give my life in its defense to protect our way of life.

Women In Aviation: The idea of serving your nation is enough to make you passionate about something. Even if it’s hard or boring, you want to stay committed to your country because it’s purposeful.

Those passengers on Flight 93 were coming home from a business trip, going to see grandma or heading out on vacation. They hadn’t gone through that preparation that I had where long before that fateful day, I had already decided that, if necessary, I was prepared to give my life to protect our way of life and nation’s defense. What’s amazing to me is that these passengers, as Americans, instinctively knew at their core that there are things more important than themselves and that they were unwilling to give in to the fear. That’s part of it. Fear is a useful signal. It tells us that there’s danger in the environment but in the end, fear is also a choice.

Do you use the fear to assess the risk and then decide whether or not you’re willing to continue to move forward towards that goal and therefore then look at those risks and take the steps to mitigate risks so that you can improve the probability of achieving that goal? That’s ultimate what risk management is about. Risk management isn’t about saying, “Here’s the reason for me not to go fly. Here’s the reason for me not to go after that goal.” Fear is a signal to risk assess and risk manage to figure out, “There’s a dangerous signal and a risk. What actions can I take to mitigate or minimize that risk so I can optimize the probability of me achieving my goal and accomplishing my mission?”

When we give in to the fear, we choose to become victims. When we give in to the fear, we disempower ourselves. We give our power away. When we give in to fear, we can no longer take positive action. Fear is a choice like bravery is a choice and a practice. Someone isn’t brave. Bravery isn’t a character attribute or something that people are born with, so rather than saying, “Be brave,” I would rather say, “Do brave. Choose brave.” It’s something that we can all daily practice. It’s a muscle. The more we choose to face our fears and be brave despite that, we become stronger and more courageous over time.

I’ve spoken to all the commanders of the Air Force, all the four stars and their MAJCOMs around the world. They always say, “What can we do for you while you’re on base?” I say, “I want to see your office.” They say, “Why?” I say, “You’ve been in the airport for many years and you’ve had so many different moves. I want to know what steel makes your wall, what photograph is still there, what memento and what challenge coins are there.”

I go into Robin Rand’s. He was a Commander of the Air Force Strike Command. I was at Barksdale for a few days and spoke at his command. I go to his office. To your point, he has a framed quote by John Wayne that says, “Courage is being scared to death and saddling up anyway.” That brings us to the third P, the Pursuit of your passion. A direct quote from one of your speeches, when you were asked why you were ready to fly this kamikaze mission, you already said, “There are things in this world that are more important than ourselves,” and then you itemized. You said freedom, the constitution of the United States, our way of life, mom, baseball, apple pie, these things are so much more important and what makes us uniquely American.

Here’s the kicker I want to focus on your last dissection of the P, Pursuit. You said, “We belong to something greater than ourselves. As complex, diverse and discordant as it is, this idea called America binds us together in citizenship, community, brotherhood and sisterhood.” To the last P, the Pursuit of your passion, going through this COVID-19 so-called crisis, what do we Americans need to do during this pause and purge to prepare ourselves for any consequential rapid change that might come our way in the future?

Fear is a signal that tells you that there’s danger in the environment, but fear is also a choice.

You rose to the occasion because of your passion, preparation and mindset. Those passengers on Flight 93 rose to the occasion because they had to. Teach us about what we need to do and why you have stayed motivated all these years to keep pursuing your passion of service before self and why all of us should do the same.

You’ve already said it. It’s because we all belong to this thing called America. What we need to hold onto and revision is when we emerge from this particular moment, we must develop together as a community and as a nation, not as two different sides or left and right but together, we need to envision what is this vision for a greater America. We can’t go back to the way things were.

Frankly, many of us wouldn’t want to go back to the way things were. The way things are with us is divided, vitriolic and full of hate. We need to figure out how we can come together, heal our nation and bring all the sides together. We’re in it together. We shouldn’t be lobbying rocks at each other. We need to figure out how do we heal our economy, communities, businesses, environments and families. This isn’t going to be easy.

One of the things that concern me is how much fear has been stoked over this virus. I’m not at all advocating that we be grossly negligent in terms of how we approach our health and how we care for our vulnerable populations but none of us get out of this life alive. When you wake up in the morning, there is risk inherent in everything that we do and we’ve been so fortunate to create a nation where we can take our safety for granted but the fact of the matter is life is not safe. If you play it safe, you never win.

I’m concerned that we are so risk-averse that we are unwilling to accept and come to terms with the fact that there will be losses but we have to go on anyways. I think about the Greatest Generation. What’s wonderful about the Greatest Generation of World War II is that they were ordinary Americans. There’s nothing great about them. They were just Americans and so fantastically courageous. The eighth air force flying B-17s was flying out of England and the European theatre going over the English Channel to take the war to the heart of Nazi Germany.

In the 1st 3.5 years of war, 1 in 5 of them would die. More of those airmen died than the entire Marine Corps across the entire globe for the whole war. Every day, they’d get into their B-17s, flying fortresses, take off and fly in sub-zero temperatures again to accomplish their mission. If you want to know fear, those men knew fear. They couldn’t move. They had to stay in their formation because that was the integrity that they needed to do to protect their squadron and group. They couldn’t maneuver defensively, so they had to every day go out and fly through the flack. They would get hit and attacked by the Messerschmitts.

Women In Aviation: Bravery isn’t something that people are born with. It’s a choice and a practice. It’s a muscle and when you choose bravery, you become stronger and more courageous over time.

The crew on those planes would be dismembered. They’d be blown up. They would see airplanes fall out of the sky. They delivered their bombs. They’d have to fight their way back home, get up the next day and do it again. Those men knew fear and that there was a good chance they weren’t going to be coming home. They were watching their buddies die and did it anyway. That’s the spirit that we need to remember. That is our heritage and legacy.

We will have losses. That’s not saying that their lives are not important or valuable but our nation, our way of life, our communities, what it means to be an American, the constitution, the rights, everything that we have built together as a nation, we cannot lose that because we are so afraid of this virus. We need to reconnect with that Greatest Generation or legacy, which is ours. It’s that courage and willingness to go forward even though we know there will be losses. Do what we can to bring our nation back and make it better when we emerge from this.

According to Heather Penney, our guest, any one of us can become a power player if we prepare mentally and emotionally before a crisis occurs. We’ll be able to respond to rapid change. That drives us to pursue our passion because we’re all going to die. We can’t take much with us except our memory that we made a difference or a legacy.

Here’s the last question. I ask this to every single one of my guests. You’re so famous for consolidating these powerful points. Professor Randy Pausch is famous for coining that speech title called The Last Lecture. Let me put you on the hot seat for a minute. If you had one day to live, what’s your consolidated message to the world? You haven’t talked about the unfair glass ceiling world in which you had to fight your way as a female fighter pilot. You didn’t even bring that up. You said, “I understand my purpose and I am going to do whatever it takes.” What’s your message to the world as we wind down?

Life is not safe. If you play it safe, you will never win.

Do brave and choose brave so that you can leave this world a better place. When we create that belonging and we realize that there are things in this world that are more important than ourselves, that allow us to exist within our highest service.

We have a chance to celebrate Mother’s Day, Father’s Day or whatever the holiday may be. My readers would be in total awesome amazement at what an amazing mother you are teaching your beautiful children exactly what you consolidated in this short episode. Thank you for your example and for being you. I cherish our friendship more than you’ll ever know.

It is so mutual. Love and hugs to you, Dan.

You’re wonderful. Remember, when you finally decide to be a power player, your power play begins in you. Until next time. As my guest, Heather Penney, has so eloquently explained in her words and in her story, quantify your takeaway and go make a power play, not just when you’re called to go airborne but because you choose to be brave. Thanks for being on the show. I can’t wait to connect offline, a virtual hug for now.

Thank you so much, Dan. Love to you and all of your readers.

Thank you so much.

Important Links:

- Heather Penney – LinkedIn

- The Last Lecture

About Heather Penny

Most widely recognized for her service on September 11, Heather “Lucky” Penney was part of the pioneering first wave of women who entered fighters directly from pilot training. Lucky was the first and only woman in the 121st Fighter Squadron during her time flying the F-16, conducting combat air patrols over Washington DC and deploying to combat twice. She was airborne the first night of initial combat for Operation Iraqi Freedom, tasked as a night-time SCUD Hunter in the western deserts of Iraq and also supporting Special Operations Forces. Lucky flew the F-16 for ten years before having to make the difficult decision to leave the fighter aviation as a single mother. Heather’s passion for aviation has never faded – she founded the first collegiate cross-country air race team, has flown her antique Taylorcraft BC-12 coast-to-coast, owned several vintage aircraft, co-piloted the B-17 Flying Fortress for the Collings Foundation, and raced jets at the Reno Air Races; she is type rated in the Gulfstream G-100 and Citation 560 series jets, and she holds CFII/MEI, and ATP ratings. Today Lucky owns and loves to fly her WWII Army Air Forces PT-13 Stearman, 1961 aerobatic Bucker Jungmann, and 1950 Cessna 170A. Heather is a passionate advocate for aviation, women in aviation, aviation history and museums, and the future of aviation. She has been inducted as an Air Force Eagle at Air University; serves is a Director of the Board for the Experimental Aircraft Association; and is on the Steering Committee for the Purdue University National Aviation Symposium.

Most widely recognized for her service on September 11, Heather “Lucky” Penney was part of the pioneering first wave of women who entered fighters directly from pilot training. Lucky was the first and only woman in the 121st Fighter Squadron during her time flying the F-16, conducting combat air patrols over Washington DC and deploying to combat twice. She was airborne the first night of initial combat for Operation Iraqi Freedom, tasked as a night-time SCUD Hunter in the western deserts of Iraq and also supporting Special Operations Forces. Lucky flew the F-16 for ten years before having to make the difficult decision to leave the fighter aviation as a single mother. Heather’s passion for aviation has never faded – she founded the first collegiate cross-country air race team, has flown her antique Taylorcraft BC-12 coast-to-coast, owned several vintage aircraft, co-piloted the B-17 Flying Fortress for the Collings Foundation, and raced jets at the Reno Air Races; she is type rated in the Gulfstream G-100 and Citation 560 series jets, and she holds CFII/MEI, and ATP ratings. Today Lucky owns and loves to fly her WWII Army Air Forces PT-13 Stearman, 1961 aerobatic Bucker Jungmann, and 1950 Cessna 170A. Heather is a passionate advocate for aviation, women in aviation, aviation history and museums, and the future of aviation. She has been inducted as an Air Force Eagle at Air University; serves is a Director of the Board for the Experimental Aircraft Association; and is on the Steering Committee for the Purdue University National Aviation Symposium.